When the FDA says… “shall establish and maintain plans”…. they are indicating that the plan needs to be documented, implemented and revised as product development progresses. Updates to the plan may be scheduled to coincide with planned phases and/or on an as needed basis. Some projects that are straight forward with low risk may only require the plan to be updated at specified intervals according to the project plan or standard operating procedures. On the other hand, in scenarios where there are technical challenges and high project risks, the plan may be updated many times to accommodate delays that are typically experienced in these situations.

Quality Systems Regulation Preamble States:

Comment 71

“This section has been revised to state that ``plans shall be reviewed, updated, and approved as design and development evolves,'' indicating that changes to the design plan are expected. A design plan typically includes at least proposed quality practices, assessment methodology, recordkeeping and documentation requirements, and resources, as well as a sequence of events related to a particular design or design category. These may be modified and refined as the design evolves. However, the design process can become a lengthy and costly process if the design activity is not properly defined and planned. The more specifically the activities are defined up front, the less need there will be for changes as the design evolves.” (FDA Preamble, 2015)

The FDA also says,…. “plans that describe or reference the design and development activities”… The regulation gives the flexibility of “describing” or making “reference” to the “design and development activities”. The FDA uses this wording to give manufacturers flexibility during development of the plans and therefore can be written for a wide range of device design complexity. For relatively simple medical devices (such as surgical gloves), the design and development plan (DDP) may fully describe in great detail all that is required to plan the development of the device. On the other hand, complex devices such as MRI machines may require a DDP that references many other sub-plans that are approved separately from the overall governing DDP. In this case sub-plans may be needed to address the development of typical aspects of the device such as software, hardware and electrical systems. Each of these areas is highly technical and complex and may need their own sub-plan to adequately define the development activities and assignments. In addition to sub-plans that reference technical aspects of the design, other typical sub-plans may include a regulatory plan, validation master plan, labeling plan, risk management plan, quality plan, detailed project schedule, etc.

The word “activities” in this regulation means just about anything that is performed by an individual or team in the process of developing the device. The “activities” (which often result in deliverables) that are required to complete development of the device should be included in the DDP. The FDA specifically states that the plan should “define responsibility for implementation” of these activities or deliverables. In simple product development projects with small teams it is ideal to assign individuals that will actually be performing the activities. In complex projects where activities are completed by teams, it is more common to see the names of the project leads or department heads that are assigned to those activities. Some companies choose to put the department names or functional groups that are assigned to the activity, but more often than not it is preferred to assign a name to the activity. When names are assigned, people take notice. It is more likely that if one person is assigned a task, they will take ownership of ensuring the activity gets completed on time. In cases when whole departments are assigned, the possibility exists that no one will take responsibility and deliverables won’t get completed on schedule.

Quality Systems Regulation Preamble States:

Comment 69

“In making this change, FDA notes that Sec. 820.20(b)(1) requires manufacturers to establish the appropriate responsibility for activities affecting quality, and emphasizes that the assignment of specific responsibility is important to the success of the design control program and to achieving compliance with the regulation. Also, the design and development activities should be assigned to qualified personnel equipped with adequate resources as required under Sec. 820.20(b)(2).” (FDA Preamble, 2015)

When the FDA states, “The plans shall identify and describe the interfaces with different groups or activities that provide, or result in, input to the design and development process, what they are really trying to say is that they want the manufacturers to thoroughly think about and plan what resources are required, how they are going to interact with each other and how are those interactions are going to effectively produce the desired result.

In practice, one of the best ways to present these interactions is in some type of matrixBP1 which correlates deliverables (or activities) vs. resources, start dates, finish dates, targeted design phase, document number of deliverables (for traceability), etc.

Quality Systems Regulation Preamble States:

Comment 70

“Many organization functions, both inside and outside the design group, may contribute to the design process. For example, interfaces with marketing, purchasing, regulatory affairs, manufacturing, service groups, or information systems may be necessary during the design development phase. To function effectively, the design plan must establish the roles of these groups in the design process and describe the information that should be received and transmitted.”

#1 Best Practice – Use matrices to communicate the interaction or correlation of information

Using matrices is often an effective method for communicating development plans to management, the development team and the FDA. During a typical inspection the FDA may review thousands of pages of documents, therefore any tools that will increase the efficiency of communicating this massive amount of information to reviewers should be implemented if possible.

As the old saying goes, “the devil is in the details.” Effective planning will allow engineers, project managers and executive management to fully understand the scope and extent of the work required to complete device development and will give management the information needed to allocate adequate resources to the project and to set realistic timelines.

Those that have worked in the medical device industry and with the FDA have come to realize that the FDA is BIG on planning, VERY big on planning, and rightly so. As a general rule, the FDA wants to see this pattern:

- Plan the activities

- Perform the planned activities

- Report what activities were actually performed and the results of the planned activities

The first step of this pattern is the planning step which also includes documents like verification and validation protocols (step two and three are implementation and reporting which will be discussed in later chapters).

When the FDA states, “The plans shall be reviewed, updated, and approved as design and development evolves,” they are trying to convey that the plan should be thoroughly understood, revised as needed, and formally approved throughout the development process.

Quality Systems Regulation Preamble States:

Comment 69

“Therefore, the approval is consistent with ISO 9001:1994 and would not be unduly burdensome since the FDA does not dictate how or by whom the plan must be approved. The regulation gives the manufacturer the necessary flexibility to have the same person(s) who is responsible for the review also be responsible for the approval of the plan if appropriate.” (FDA Preamble, 2015)

It is best practice to have a draft versionBP2 of the design and development plan (DDP) which should typically be reviewed individually and in design reviews. Prior to approval of the DDP, the approvers should be given sufficient time to read and understand the DDP content and intent of the plan. After reviewers have had the opportunity to read the DDP, it is best practiceBP3 to review the DDP during a design review which will give all attendees the opportunity to address (or challenge) any concerns or issues that may arise. As a result of the review, decisions will be made and actions will be assigned that may require updates to the DDP. This may include changing unrealistic target dates, deliverable assignments or updates with new requirement deliverables.

#2 Best Practice – Have documents in draft status for design review prior to approval

To increase the efficiency of the review and approval process, “near final” drafts of documents (prior to design review) should be reviewed by the design review attendees. After the results of the design review are documented, the drafts of the documents can be easily updated and then approved to reflect the outcome of the design review.

#3 Best Practice – Reviewers should be given sufficient time to review documents prior to design reviews and approval.

Reviewers should be given sufficient time to review all documents prior to approving and holding a design review. If insufficient time is provided, reviewers may be inadequately prepared for design review discussion and/or individual review prior to document approval.

It is important to understand that the DDP should be used as a living document. Just as product development can never be perfectly planned from the beginning, neither can the DDP be completely and accurately written to predict the future. As required changes in the development process occur, the plan should be updated periodically. The FDA is very aware that product development is often unpredictable and that plans often change. As a matter of fact, the FDA expects to see multiple revisions of the DDP and may be suspicious if it was never revised. The decision to update the DDP should be based heavily on when significant changes to the development of the product are required. The DDP should be updated as discussions of deviating from the current approved plans become finalized.

Typically the initial version of the DDP may only include the initial plans that are known at that point in time and therefore the plan will have relatively minimal content. As product development progresses the plan should be updated as additional information becomes available. As an example, the initial revision of the DDP may include deliverable dates that are specified by quarters of the year (3 month time period). As the target dates get closer and more confidence and understanding of the deliverable requirements are understood, the deliverable date will most likely be able to be refined within a month, week or even a specific day.

Approval of the DDP (as well as other documents) is typically performed by a handwritten signature and date or by an electronic signature (see 21 CFR part 11), either of which is an acceptable document approval method. If hand written signatures are used for approval it is best practice to provide the printed name next to the signature line to allow easy association of names with signatures if required during an FDA inspection or internal audit. Either type of approval method is acceptable as long as 21 CFR part 11 is followed for electronic signatures on a validated software system. These approval methods are applicable for all design and development documents that are subject to FDA inspection.

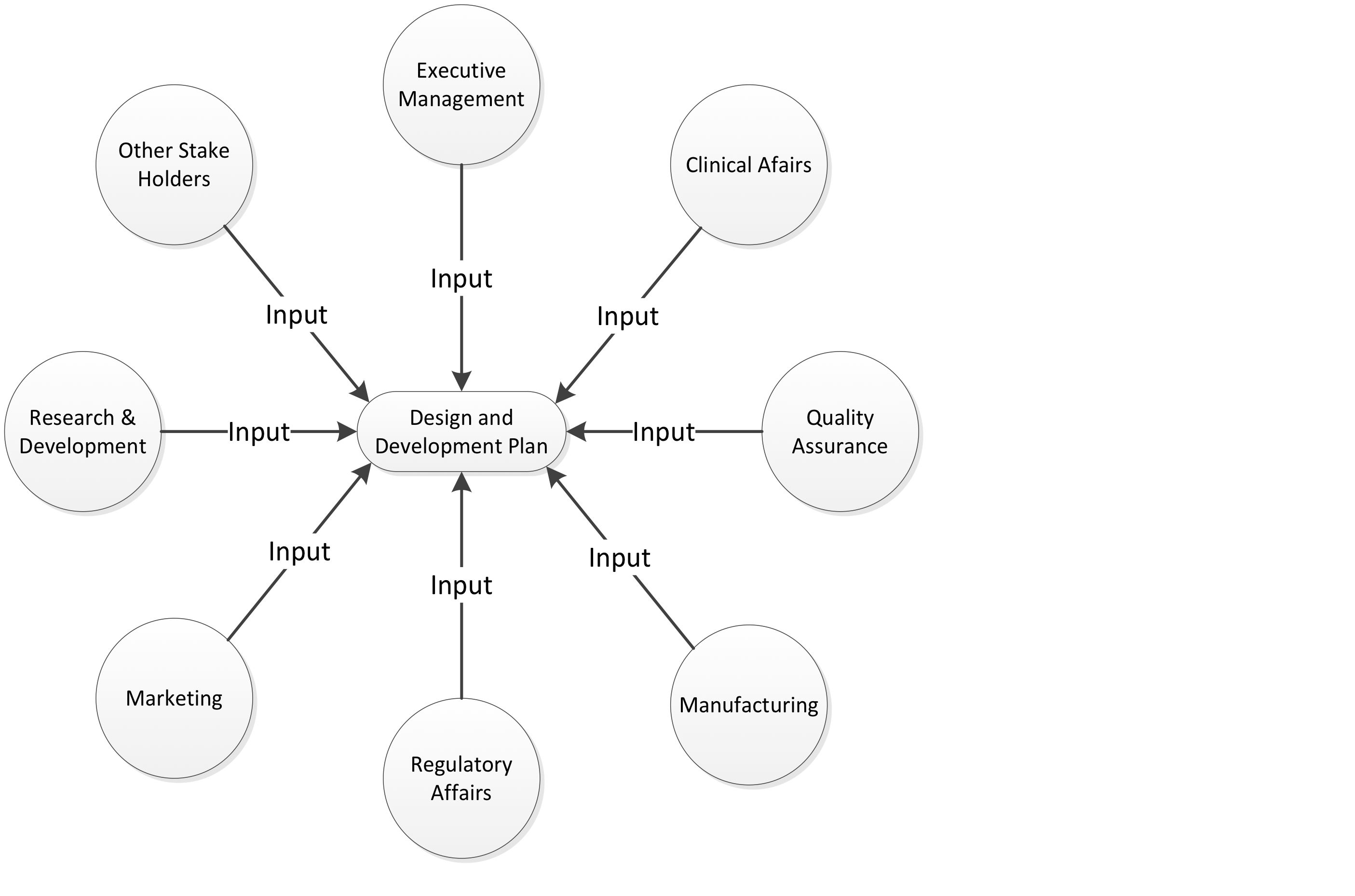

The development activities and resource assignments indicated in the DDP typically affect many departments and therefore require a greater number of approval signatures than other development documents (e.g. risk assessments, design inputs, verification protocols). In small to medium size companies, approvals will typically include executive level management members such as VP of Quality, VP of Engineering, VP of Marketing and VP of Regulatory Affairs. In larger corporations, lower to mid-level management will typically approve the DDP. The intent of having executive management approve the DDP is twofold: 1) To receive management’s approval of the team’s plan to develop the product 2) To receive approval of resources (e.g. people, money, equipment) that the project manager has requested. Other department heads and Stakeholders should also be considered as approvers and/or to provide input to the DDP as appropriate for the organization. The FDA does not directly specify that the stakeholders are required to approve the DDP but they do indicate under 21 CFR 820.20 (Subpart B, Management Responsibility) that management should be involved and aware of activities pertaining to the quality system. Figure 6 below indicates typical stakeholders that will have significant input to the DDP.

It should be noted that the previous paragraph stated “the team’s plan” should be approved by management. This is a key concept that needs to be accepted and understood by management for product development teams to be successful. In smaller companies, executive management has a tendency to directly manage and influence development plans. As companies grow, this becomes impractical, inefficient and unwise. Management’s role should not include extending significant influence in directing detailed development plans. Management has the best intentions, but they are often too far removed from the technical hurdles and detail work that is required to effectively develop the DDP. The team is in the trenches every day, and they are therefore realistic with their target dates and are greatly in tune with technical challenges and risks that are just around the corner.

Ideally an executive sponsor will develop a project charter in conjunction with the project manager to establish high level requirements that will initially be approved by executive management. The project manager will present these requirements to the team who will in turn develop a DDP with realistic target dates and resource plans. During the review of the DDP, management will typically either cut requested resources or reduce development time from the proposed plan. If resources and/or time are cut from the plan, it is up to the team (primarily the project manager) to communicate the impact to the target launch data as a result of the resources being denied. This situation epitomizes one of the reasons the FDA requires a DDP. At this point in the review and approval process of the DDP, a cross functional team and executive management have to come to a consensus as to what should and can be realistically accomplished to meet all stakeholder requirements. If a review of the DDP is thoroughly performed, the final version of the DDP may go through multiple revisions before all stakeholders are satisfied. On the other hand if the DDP always flies through the approval process on the first draft and stakeholders are not invested in the plan, the DDP is a plan on paper only and becomes ineffective and a waste of time. This typically happens when management is only concerned about “checking the regulatory box” to meet regulatory requirements but is not interested in using the DDP as an effective planning tool.

Even though getting the DDP through the approval process may seem as difficult as getting an act of Congress passed, in the end, the team and management can have confidence that the plan has been thoroughly reviewed and vettedBP4. This type of rigorous review gives the proposed design greater potential for being a successful product, not to mention being compliant to the regulations.

#4 Best Practice – The DDP should be thoroughly reviewed and vetted.

If approvers of the DDP are not fully invested in the plan, the development of the product will suffer and the safety and effectiveness of the device may be compromised. Management should establish a culture in the organization which prioritizes the development of effective design and development plans. This will greatly benefit the success of the product and compliance to regulatory requirements.

3.6.1 Quality Systems Manual: Design and Development Planning

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

Excerpt from the “Quality Systems Manual: A Small Entity Compliance Guide”

(Withdrawn from FDA website 12 December 2013)

(FDA QS Manual, 2013)

Developing a new device and introducing it into production are very complex tasks. For many new devices and associated manufacturing processes that use software, these tasks are further complicated because of the importance of software, and the possibility of subtle software errors. Without thorough planning, program control, and design reviews, these tasks are virtually impossible to accomplish without errors or leaving important aspects undone. The planning exercise and execution of the plans are complex because of the many areas and activities that should be covered. Some of the key activities are:

- determining and meeting the user/patients requirements;

- meeting regulations and standards;

- developing specifications for the device;

- developing, selecting and evaluating components and suppliers;

- developing and approving labels and user instructions;

- developing packaging;

- developing specifications for manufacturing processes;

- verifying safety and performance of prototype and final devices;

- verifying compatibility with the environment and other devices;

- developing manufacturing facilities and utilities;

- developing and validating manufacturing processes;

- training employees;

- documenting the details of the device design and processes; and,

- if applicable, developing a service program.

-

To support thorough planning, the QS regulation requires each manufacturer to establish and maintain plans that describe or reference the design and development activities and define responsibility for implementation.

The plans should be consistent with the remainder of the design controls. For example, the design controls section of the quality system requires a design history file (DHF) [820.30(j)] that contains or references the records necessary to demonstrate that the design was developed in accordance with the:

- approved design plan, and

- regulatory requirements.

Thus, the design control plans should agree with, and require meeting, the quality system design control requirements. One of the first elements in each design plan should be how you plan to meet each of the design control requirements for the specific design you plan to develop; that is, the design plans should support all of the required design control activities. Such plans may reference the quality system procedures for design controls in order to reduce the amount of writing and to assure agreement.

Interface

Design And Development Planning section 820.30(b) states:

“The plans shall identify and describe the interfaces with different groups or activities that provide, or result in, input to the design and development process...”

If a specific design requires support by contractors such as developing molds, performing a special verification test, clinical trials, etc., then such activities should be included or referenced in the plan and proactively implemented in order to meet the interface and general quality system requirements. Of course, the interface and general requirements also apply to needed interaction with manufacturing, marketing, quality assurance, servicing or other internal functions.

Proactive interface is a important aspect of concurrent engineering. Concurrent engineering is the process of concurrently, to the maximum feasible extent, developing the product and the manufacturing processes. This valuable technique for reducing problems, cost reduction and time saving cannot work without proactive interface between all involved parties throughout all stages of the development and initial production program.

Structure of Plans

Each design control plan should be broad and complete rather than detailed and complete. The plan should include all major activities and assignments such as responsibility for developing and verifying the power supplies rather than detailing responsibility for selecting the power cords, fuse holders and transformers. Broad plans are:

- easier to follow;

- contain less errors;

- have better agreement with the actual activities; and

- will require less updating than detailed plans.

Over the years, several manufacturers have failed to follow this advice and opted for writing detailed design control procedures. They reported being unable to finish writing the over-detailed procedures and were unable to implement them.

Regardless of the effort in developing plans, they usually need updating as the development activities dictate. Thus, the QS regulation requires in 820.30(a) that the plans shall be reviewed, updated, and approved as the design and development evolves. The details of updating are left to the manufacturer; however, the design review meetings are a good time and place to consider, discuss and review changes that may need to be made in the design development plan.